Tinubu estate land dispute: Firm seeks Appeal Court nod to challenge consent judgment

A fresh legal battle has emerged over a vast swathe of land, located at Ogombo, tied to the historic estate of the late Madam Iyalode Efunroye Tinubu, as Adamakin Investment and Works Limited and its chief executive, Chief Akinfolabi Akindele, have approached the Court of Appeal in Lagos seeking permission to challenge a controversial consent judgment that ceded more than 114 hectares of the estate’s land to a group of individuals.

In a motion on notice filed by their counsel, Mohammed Idris, the appellants/applicants are asking the appellate court for multiple reliefs, including extension of time to seek leave to appeal, permission to appeal as interested parties, and an order staying execution of the consent judgment delivered by Justice O. O. Ogunjobi of the Lagos High Court, Tafawa Balewa Square (TBS), on November 12, 2024, in Suit No. LD/12881LMW/22.

The judgment in question arose from a case between Mr Shafiu Kassim Lumosa and others versus “Unknown Person” and others, which, according to the applicants, was settled under circumstances they describe as fraudulent and prejudicial to their interests.

In the motion, Adamakin Investment and Chief Akindele insist they have a proprietary and financial stake in the land at the heart of the dispute by powers of attorney granted to them by court-appointed trustees of Madam Tinubu’s estate in 2004 and 2012.

According to the applicants, “By virtue of the said Power of Attorney, the applicants are to manage the family houses and landed properties which include entering into contracts to develop any vacant or undeveloped land, to regularise titles, and commence and prosecute actions on behalf of the estate.”

They added that under the arrangement, they are entitled to 40 per cent of the landed properties in the estate “to cover our expenses and entitlement in the preservation and management of the properties, including the land in this case.”

Chief Akindele, in a sworn affidavit, said they had “expended large sums of money on the estate to preserve and protect the landed properties, including surveying of the land, as well as prosecution of cases in respect of the land.”

The applicants allege that the consent judgment was orchestrated by some of the named respondents “in a bid to deprive the applicants of their legitimate and accrued rights in the land under the Power of Attorney.”

According to Akindele’s affidavit: “It was discovered that the suit had been instituted in the names of the 1st and 2nd respondents who had purportedly conceded to a consent judgment ceding about 114.476 hectares of the estate land to the 3rd–7th respondents without the applicants’ knowledge and at gross undervaluation.

He further claimed that when confronted, the sole surviving trustee of the estate, the 1st respondent, denied knowledge of the case or involvement in any negotiations, and disowned the signature appearing in the settlement terms.

The affidavit also stated that other family members of Madam Tinubu “were not aware of this case or any agreement to cede any portion of land” and expressed strong disapproval upon learning of it.

The applicants said they initially acted on instructions from the 1st respondent to challenge the judgment.

Akindele claimed he was told to engage lawyers “to halt any enforcement process and to take immediate steps to set aside the consent judgment.”

On that basis, their counsel filed a motion for a stay of execution. But, according to the affidavit, the effort collapsed after the respondents filed a counter-affidavit denying that such instructions had ever been given.

The stay application was eventually withdrawn and struck out.

“It was upon the reaction of the respondents to the motion for stay that it dawned on us that the 1st and 2nd respondents colluded in selling the land to the 3rd–7th respondents to deprive us of our share,” Akindele stated.

The disputed property forms part of “Ewe Agbigbo/Iwaya Farm Land,” a vast tract associated with Madam Tinubu, a 19th-century Yoruba merchant, political leader, and philanthropist.

Court records referenced in the affidavit stated that the land was surveyed by nationalist leader, Herbert Macaulay, in 1911 and 1912, with the plan tendered as evidence in a 1912 case — Fafunmi v. Osun Apena.

An order by Justice S. A. Adebajo of the Lagos High Court in 2002 appointed four trustees to oversee the estate, three of whom have since died, leaving the 1st respondent as the sole surviving trustee.

The applicants told the Court of Appeal they only became aware of the case and judgment in February 2025, when consultants inspecting the land for title formalisation discovered the development.

They say this was well after the three-month constitutional window for filing an appeal had expired.

In his affidavit, Akindele explained: “We were not aware of the pendency of the case or the entering of the consent judgment until sometime in February 2025.

“It was after the 1st respondent denied having instructed us to appeal that we realised we had to pursue our rights independently of the 1st respondent and immediately instructed counsel to do so.”

The applicants also cited illness on the part of their counsel, M. D. Idris, as another factor causing delay, attaching medical reports as evidence.

The motion lists several legal grounds for the application, including:

“That the applicants’ proprietary rights were directly affected by the consent judgment.

“That they were not parties to the original suit and thus could not have appealed without leave.

“That the proceedings and judgment amounted to a denial of their constitutional right to a fair hearing.

“That the consent judgment was “a fraud” on them and should not be allowed to stand.”

They further argued that because it was a consent judgment, leave of the Court of Appeal is required before an appeal can be filed.

“Our grounds of appeal raise fundamental issues going to jurisdiction of the trial High Court, which has no power to deprive a litigant of his proprietary rights without affording him an opportunity for a fair hearing,” the applicants’ motion states.

The applicants are asking the appellate court to: Extend time for them to seek leave to appeal as interested parties, grant them leave to appeal as interested parties, extend time to appeal against the consent judgment, and stay execution of the judgment pending appeal.

They also seek “such further order or orders as the court may deem fit to make.

As of the time of filing this report, the respondents, including members of the prominent Kosoko family, had yet to file a reply to the fresh application at the appellate court.

However, in their earlier position at the High Court, they denied allegations of fraud and maintained that the consent judgment was valid.

Oloja-Elect drags Oba of Lagos, police to court over alleged harassment, land dispute.

Oloja-Elect drags Oba of Lagos, police to court over alleged harassment, land dispute.  Adamakin Investment And Works Ltd Demands Retraction And Apology From EFCC over False Ponzi Scheme

Adamakin Investment And Works Ltd Demands Retraction And Apology From EFCC over False Ponzi Scheme  Don’t transact in disputed Lekki estate, firm warns buyers

Don’t transact in disputed Lekki estate, firm warns buyers  Lagos govt raises alarm as thousands ignore CofO applications

Lagos govt raises alarm as thousands ignore CofO applications  Tensions Rise in Mushin as APC Aspirant Alleges Plot to Impose Candidate

Tensions Rise in Mushin as APC Aspirant Alleges Plot to Impose Candidate  Legal Tussle Emerges Over Efunroye Tinubu Estate as Counsel Warns IGP Monitoring Unit

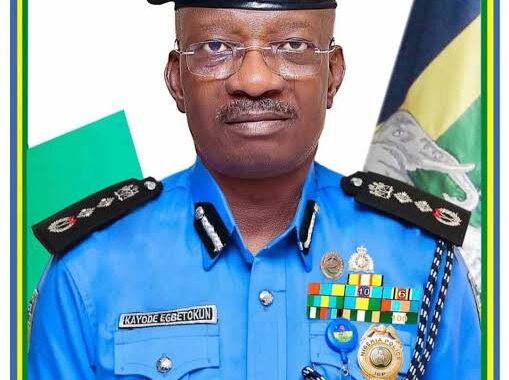

Legal Tussle Emerges Over Efunroye Tinubu Estate as Counsel Warns IGP Monitoring Unit